Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Tuesday, June 2, 2009

Excellence in Education

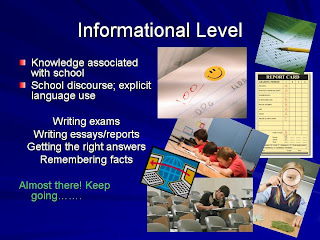

I recently saw a video clip that featured Dr. Asa Hillard, a former professor at Georgia State University. He was speaking about a course that he taught to graduate students entitled, Excellence in Urban Education. The course looked at excellence that has already been achieved- the focus being on what has worked and continues to work and learning from it instead of being “preoccupied with excuses that pretend to explain why the traditionally low performing are unable to reach excellence.” Most of us may be well-intentioned, but we do make a lot of excuses when students are not achieving. In our defence, however, we are not always aware of the issues surrounding the problem. We may understand them on a surface level only. How then can we find a solution for helping our underachieving students if we do not really understand why they are underachieving in the first place? As Finn states in his book, Literacy with an Attitude, “Savage inequalities persist because a lot of well-meaning people are doing the best they can, but they simply do not understand the mechanisms that stack the cards against so many children.” (Pg. 94) I believe accepting the notion of “doing the best we can” is simply not good enough anymore. The questions we should be asking ourselves everyday are, “How do we help students acquire powerful literacy so that they can reach excellence?” and “How do we help them help themselves?” As Finn states in his final chapter, “In order for there to be significant progress, those ultimately injured by the problem, the working class themselves, must take a hand.” (Pg. 196). This reminds me of the proverb, “If you give a man a fish, he can eat for a day. If you teach a man to fish, he can eat for a lifetime.” Let’s stop just imparting knowledge and curriculum to our students and teach them in a way that will help them progress to the powerful literacy they require to become life-long learners. Let’s make learning authentic and relevant to their lives so they don’t see it as just a means to an end. I believe this is what will empower students to eventually help themselves and others in their communities. So how are we supposed do this? Firstly, we have to begin by recognizing and understanding the problem. When we understand it, then we need to ensure that our students understand it as well. For example, most people in the working classes often use ‘implicit language’ when communicating with others in their communities. The language of our schools, however, is typically ‘explicit’ and therefore puts the working class students at a great disadvantage. Knowing this is very important for us as educators because we can better understand why students struggle with the discourse in our schools. School discourse is something, I think, we all take for granted. As Finn discovered, “The teachers began to realize that they had been expecting school discourse; they were not teaching it.” (Pg. 149) We need to teach it explicitly so that we can put the working class students on an even playing field with the others who have already been exposed to explicit language and school discourse before entering school. Secondly, we have to be open to the possibility that things can change no matter how bleak the situation appears. Positive thinking breeds positive results. Hard work and collaborative planning helps as well, so does learning from those who have already been successful and trying it out in our classrooms. Let’s stop reinventing the wheel and start working smarter. Finally, we don’t give up until our students achieve excellence. Does this seem idealistic? Perhaps it does, but isn’t it always better to work towards the ideal? Aren’t our students worth it? This reminds me of something I think about every time we discuss graduation rates at our Student Success meetings. The Ministry of Education has set a target graduation rate in Ontario of 85% by the year 2010. Many teachers often lament that this is much too lofty a target. I, on the other hand, can’t help but think of the 15% who will not be successful. What about them? We constantly talk about “success for all”, but do we really mean it? Are we going to practice what we preach or are we just going to continue to be satisfied with ‘doing our best’? I recently heard Sir Michael Barber, Partner McKinsey & Company, speak about our moral purpose as it pertains to Literacy and Numeracy education. He believes that knowledge on its own is not power. In his words, “Power is knowledge combined with the capacity to think combined with the confidence to intervene at the moment when it makes a difference.” That is the powerful literacy we want for our students. Are we, as teachers, up for this challenge? Do we have the confidence to intervene at the moment it makes a difference? I will continue to be optimistic and believe that we do. Let’s begin by discarding every excuse ever presented and just get down to the business of ensuring excellence in education for all students! That is our moral purpose as educators.

I recently saw a video clip that featured Dr. Asa Hillard, a former professor at Georgia State University. He was speaking about a course that he taught to graduate students entitled, Excellence in Urban Education. The course looked at excellence that has already been achieved- the focus being on what has worked and continues to work and learning from it instead of being “preoccupied with excuses that pretend to explain why the traditionally low performing are unable to reach excellence.” Most of us may be well-intentioned, but we do make a lot of excuses when students are not achieving. In our defence, however, we are not always aware of the issues surrounding the problem. We may understand them on a surface level only. How then can we find a solution for helping our underachieving students if we do not really understand why they are underachieving in the first place? As Finn states in his book, Literacy with an Attitude, “Savage inequalities persist because a lot of well-meaning people are doing the best they can, but they simply do not understand the mechanisms that stack the cards against so many children.” (Pg. 94) I believe accepting the notion of “doing the best we can” is simply not good enough anymore. The questions we should be asking ourselves everyday are, “How do we help students acquire powerful literacy so that they can reach excellence?” and “How do we help them help themselves?” As Finn states in his final chapter, “In order for there to be significant progress, those ultimately injured by the problem, the working class themselves, must take a hand.” (Pg. 196). This reminds me of the proverb, “If you give a man a fish, he can eat for a day. If you teach a man to fish, he can eat for a lifetime.” Let’s stop just imparting knowledge and curriculum to our students and teach them in a way that will help them progress to the powerful literacy they require to become life-long learners. Let’s make learning authentic and relevant to their lives so they don’t see it as just a means to an end. I believe this is what will empower students to eventually help themselves and others in their communities. So how are we supposed do this? Firstly, we have to begin by recognizing and understanding the problem. When we understand it, then we need to ensure that our students understand it as well. For example, most people in the working classes often use ‘implicit language’ when communicating with others in their communities. The language of our schools, however, is typically ‘explicit’ and therefore puts the working class students at a great disadvantage. Knowing this is very important for us as educators because we can better understand why students struggle with the discourse in our schools. School discourse is something, I think, we all take for granted. As Finn discovered, “The teachers began to realize that they had been expecting school discourse; they were not teaching it.” (Pg. 149) We need to teach it explicitly so that we can put the working class students on an even playing field with the others who have already been exposed to explicit language and school discourse before entering school. Secondly, we have to be open to the possibility that things can change no matter how bleak the situation appears. Positive thinking breeds positive results. Hard work and collaborative planning helps as well, so does learning from those who have already been successful and trying it out in our classrooms. Let’s stop reinventing the wheel and start working smarter. Finally, we don’t give up until our students achieve excellence. Does this seem idealistic? Perhaps it does, but isn’t it always better to work towards the ideal? Aren’t our students worth it? This reminds me of something I think about every time we discuss graduation rates at our Student Success meetings. The Ministry of Education has set a target graduation rate in Ontario of 85% by the year 2010. Many teachers often lament that this is much too lofty a target. I, on the other hand, can’t help but think of the 15% who will not be successful. What about them? We constantly talk about “success for all”, but do we really mean it? Are we going to practice what we preach or are we just going to continue to be satisfied with ‘doing our best’? I recently heard Sir Michael Barber, Partner McKinsey & Company, speak about our moral purpose as it pertains to Literacy and Numeracy education. He believes that knowledge on its own is not power. In his words, “Power is knowledge combined with the capacity to think combined with the confidence to intervene at the moment when it makes a difference.” That is the powerful literacy we want for our students. Are we, as teachers, up for this challenge? Do we have the confidence to intervene at the moment it makes a difference? I will continue to be optimistic and believe that we do. Let’s begin by discarding every excuse ever presented and just get down to the business of ensuring excellence in education for all students! That is our moral purpose as educators.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)